February 16, 2026

If you have any feedback on this article or are interested in subscribing to our content, please contact us at opinions@muzinich.com or fill out the form on the right hand side of this page.

--------

Last week got off to a flying start, building on a strong close from US equities the preceding Friday (6th February) and gaining further momentum at the London open on Monday (9th February) with news from Japan that Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s gamble to dissolve the lower house and call a general election had paid off spectacularly, delivering a historic landslide for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The LDP secured 316 of the 465 seats in the House of Representatives, a gain of 118 seats, and marked the first time in postwar Japan a single party has achieved a two-thirds majority. Together with its junior partner, the Japan Innovation Party, the ruling bloc now controls 352 seats, or about 76% of the chamber, giving it the power to override upper house vetoes and govern without ad hoc opposition support.[1]

This decisive victory significantly strengthens Sanae Takaichi’s political mandate, which is oriented towards growth and favours proactive fiscal expansion to ease cost-of-living pressures, alongside state-led investment across 17 strategic industries. It also reinforces support for nuclear power and a firmly pro-US foreign policy.

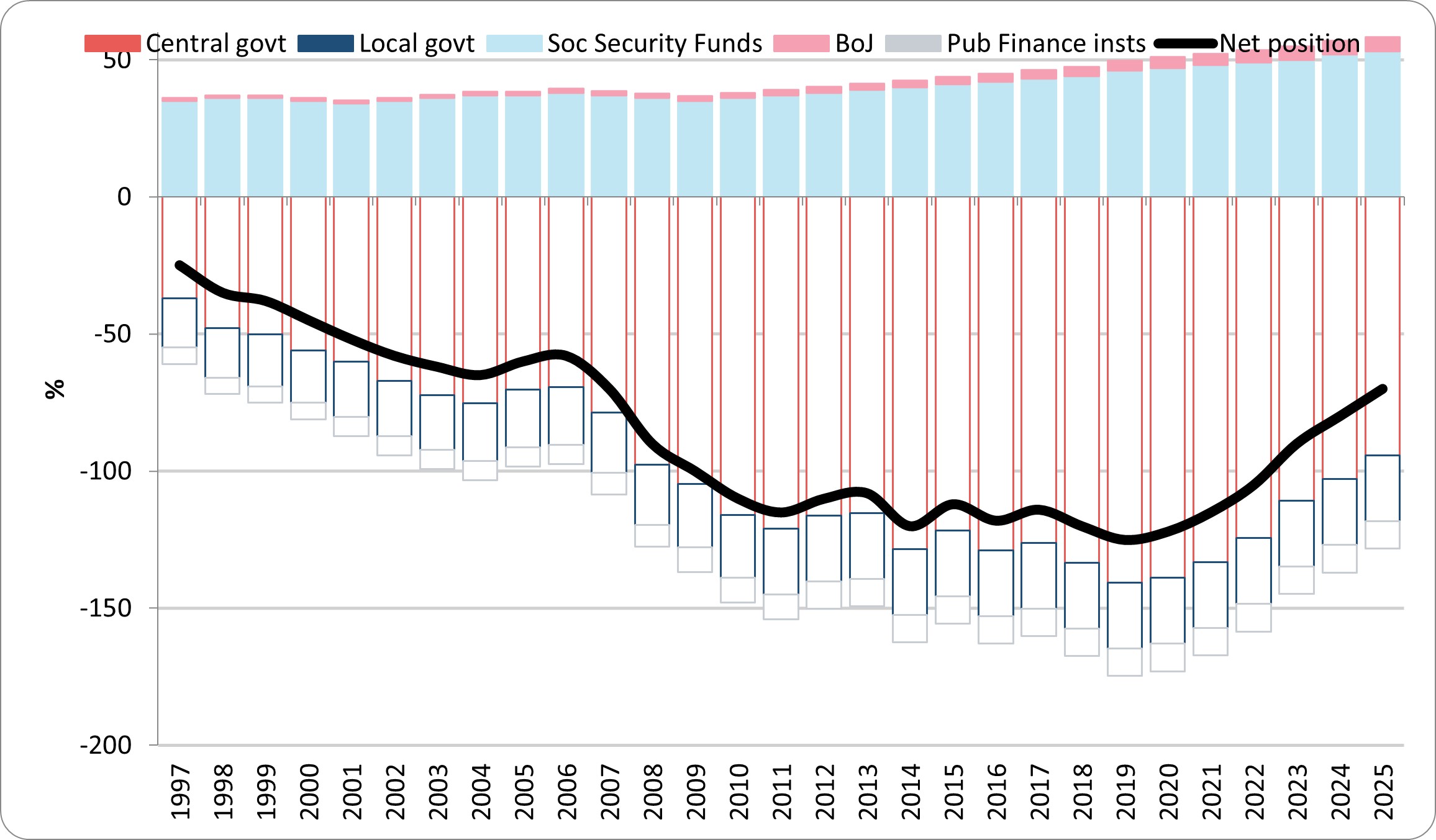

Investor concerns now center on how Sanae Takaichi plans to fund the proposed ¥21 trillion stimulus package and her pledge to suspend the 8% sales tax on food for two years.[2] Commentators have amplified these worries by pointing to Japan’s heavy public debt burden, with debt around 235% of GDP.[3]

However, as corporate credit investors at Muzinich, we assess leverage risk not only on a gross debt basis, but also in net terms. Viewed through a net debt lens, Japan’s position looks markedly different. Once government assets are taken into account – that is, net debt equals government liabilities minus government assets – net debt is closer to 65% of GDP.[3] From this perspective, one could ask: does Japan really have a debt problem? (see Chart of the Week). It is notable the reduction in net debt began in 2020, coinciding with a weaker yen and a strong rally in global equity markets. In effect, Japan is structurally short yen and long risk assets, funded domestically at a very low cost.

This leads us to conclude that a sharp, extended appreciation of the yen should be of greater concern to investors than gross debt levels, while in a systemic risk-off environment, Japan may no longer serve as the safe haven it once did, given the sovereign’s long-equity positioning. However, gross debt should not be ignored, as a rising debt stock increases servicing costs, which will absorb an ever-growing share of fiscal revenues, weighing on long-term growth that is already under pressure due to Japan’s demographic challenges.

In the short term, investors gave Japan’s administration a full vote of confidence. The yen closed the week as the best-performing G10 currency against the US dollar, Japan’s equity market led global peers with the Nikkei 225 up more than 5%, and long-end Japanese government bond yields – the part of the curve most sensitive to fiscal largesse – fell by around 11 basis points (bps).

As the week progressed, last week’s ocean swells began to generate choppier waters, with our preferred volatility indices, the VIX and MOVE, both spiking higher, suggesting rising uncertainty and waning confidence.

For the UK, the key concern is growth. In the fourth quarter of 2025, the economy expanded by just 0.1%, marking a second consecutive quarter of weak growth. A closer look at the expenditure breakdown shows that government consumption in the fourth quarter was the primary driver of expansion. As a result, the economy grew by 1.4% in 2025, slightly faster than the 1.1% recorded in 2024, and broadly in line with the eurozone, which also grew by 1.4% in 2025.[4] However, the lack of positive momentum over the second half of 2025 leaves the outlook for 2026 pessimistic. The Bank of England projects growth of 0.9%, while the Bloomberg consensus forecast is around 1.0%.[5]

There is no single cause of the UK’s economic difficulties, but at the core lies a sustained shift of resources from the private to the public sector. Record-high taxes, particularly on businesses, rising regulatory burdens and continued government borrowing are absorbing an ever-larger share of private savings. As the state claims a growing proportion of national income, less capital flows to households and firms, encouraging cutbacks in consumption and investment, weighing on growth and ultimately eroding the economy’s long-term growth potential. Investors are now bringing forward expectations of Bank of England policy easing next month, with markets pricing in a 72% probability.[6]

For the US, it was a major week for economic data, with retail sales, non-farm payrolls and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) all released in the same week, an unusually rare occurrence. Given that each of these reports has the potential to move financial markets significantly, government agencies typically stagger their release across separate weeks.

US retail sales unexpectedly stalled in December, with eight of the 13 retail categories posting declines. Control-group sales, which feed directly into the government’s calculation of goods spending for GDP, unexpectedly fell by 0.1%, suggesting consumers ended the year on a softer note. However, it is likely that heavy Black Friday discounting capped December sales. Given the strong pace of consumer spending heading into the holiday season, the weaker December figures more likely reflect demand being pulled forward rather than a genuine deterioration in underlying consumption.[7]

At first glance, the non-farm payrolls report delivered a sizeable upside surprise, with 130,000 jobs created in January, well above the 65,000 consensus forecast, marking the strongest monthly gain in more than a year and pushing the unemployment rate down to 4.3%. A closer look, however, shows that the breadth of job growth was limited. Hiring was dominated by healthcare, which added 137,000 jobs, its strongest increase since 2020. That said, it was encouraging to see construction and business services also adding jobs, while manufacturing recorded its first monthly employment increase in over a year. Offsetting these gains, federal government payrolls fell by 42,000 and financial services shed around 22,000 jobs. Overall, the report pointed to continued stabilization in the US labour market at the start of 2026.[8]

As for the January consumer price report, for a month that typically sees firmer price pressures as businesses raise prices at the start of the year, this pattern did not hold in 2026, suggesting peak inflationary pressures are now well behind us. Headline CPI rose just 0.17% in January, down from 0.30% in December and well below the 0.30% consensus expectation. At the same time, core CPI increased 0.30%, broadly in line with forecasts. Both readings were notably softer than the average January increases of the past three years. On a year-over-year basis, headline inflation fell sharply to 2.4% from 2.7%, while core inflation edged down to 2.5% from 2.6%.[9]

Overall, the reports paint a picture of stabilization and limited pricing pressures, and there was nothing in the data to prevent the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) from continuing to adjust policy rates toward neutral levels. The overnight interest rate swap market is implying the policy rate will fall to around 3% by year-end.[6] Investors appear to agree, with US Treasuries as the best-performing asset of the week and 30-year yields falling by 14 bps.

Normally, one would expect this to be a “green light” for US equity markets, but the ongoing swell from the technology sector continues to keep equities choppy as investors nervously scrutinize capital spending by hyperscalers and the disruptive implications of artificial intelligence. This week, shares in wealth management firms fell after Altruist announced a new AI-powered tool, claiming it can deliver fully personalized tax strategies in minutes.[10] The resulting uncertainty left the US dollar and US equities as the underperformers of the week, with pressure concentrated in the technology sector. For example, the Dow Jones is up more than 3% year-to-date and sits within 1% of its all-time high, while the so-called Magnificent Seven are down by over 6%, highlighting where concerns are situated.

Chart of the Week: What Debt Problem? Japanese government net debt 64.9%

Source: IMF Public Finances in Modern History database, as published in the Financial Times, February 9, 2026. For illustrative purposes only.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current or future results.

References to specific companies is for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect the holdings of any specific past or current portfolio or account.

This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The opinions expressed by Muzinich & Co. are as of February 13, 2026, and may change without notice. All data figures are from Bloomberg, as of February 13, 2026, unless otherwise stated.

References

[1] Bloomberg, “Takaichi Poll Triumph Centralizes Japan Policy, Aids Tech: React,” February 8, 2026

[2] The Guardian, “Japanese shares hit record high as Sanae Takaichi wins landslide election victory,” February 9, 2026

[3] Financial Times, “Japan LLC has been trading its way out of a fiscal hole,” February 9, 2026

[4] Bloomberg, “UK REACT: Surprise GDP Weakness Fleeting, Better News Ahead,” February 12, 2026

[5] Bloomberg, as of February 13, 2026

[6] Bloomberg, as of February 13, 2026

[7] Bloomberg, “US Retail Sales Unexpectedly Stalled to Close Holiday Season,” February 10, 2026

[8] Bloomberg, “US Employment Change By Industry for January,” February 11, 2026

[9] Bloomberg, “US REACT: Cooler January CPI Than Usual Is a Win for Fed Cuts,” February 13, 2026

[10] Citywire, “US wealth manager stocks tumble on AI tax tool launch news,” February 11, 2026

--------

Important Information

Muzinich & Co., “Muzinich” and/or the “Firm” referenced herein is defined as Muzinich & Co. Inc. and its affiliates. This material has been produced for information purposes only and as such the views contained herein are not to be taken as investment advice. Opinions are as of date of publication and are subject to change without reference or notification to you. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current or future results and should not be the sole factor of consideration when selecting a product or strategy. The value of investments and the income from them may fall as well as rise and is not guaranteed and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Rates of exchange may cause the value of investments to rise or fall. Emerging Markets may be more risky than more developed markets for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to, increased political, social and economic instability, heightened pricing volatility and reduced market liquidity. Any research in this document has been obtained and may have been acted on by Muzinich for its own purpose. The results of such research are being made available for information purposes and no assurances are made as to their accuracy. Opinions and statements of financial market trends that are based on market conditions constitute our judgment and this judgment may prove to be wrong. The views and opinions expressed should not be construed as an offer to buy or sell or invitation to engage in any investment activity, they are for information purposes only. Any forward-looking information or statements expressed in the above may prove to be incorrect. In light of the significant uncertainties inherent in the forward-looking statements included herein, the inclusion of such information should not be regarded as a representation that the objectives and plans discussed herein will be achieved. Muzinich gives no undertaking that it shall update any of the information, data and opinions contained in the above.

United States: This material is for Institutional Investor use only – not for retail distribution. Muzinich & Co., Inc. is a registered investment adviser with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Muzinich & Co., Inc.’s being a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC in no way shall imply a certain level of skill or training or any authorization or approval by the SEC.

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (excluding the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM): This document, and the information contained herein, does not constitute, and is not intended to constitute, a public offer of securities in the United Arab Emirates (“UAE”) and accordingly should not be construed as such. The Units are only being offered to a limited number of exempt Professional Investors in the UAE who fall under one of the following categories: federal or local governments, government institutions and agencies, or companies wholly owned by any of them. The Units have not been approved by or licensed or registered with the UAE Central Bank, the SCA, the Dubai Financial Services Authority, the Financial Services Regulatory Authority or any other relevant licensing authorities or governmental agencies in the UAE (the “Authorities”). The Authorities assume no liability for any investment that the named addressee makes as a Professional Investor. The document is for the use of the named addressee only and should not be given or shown to any other person (other than employees, agents or consultants in connection with the addressee’s consideration thereof).

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (including the Dubai International Financial Centre and the Abu Dhabi Global Market): This information does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe for or purchase, any securities or investment products in the UAE and accordingly should not be construed as such. Furthermore, this information is being made available on the basis that the recipient is an entity fully regulated by the ADGM Financial Services Regulatory Authority (FSRA), and acknowledges and understands that the entities and securities to which it may relate have not been approved, licensed by or registered with the UAE Central Bank, the Dubai Financial Services Authority, the UAE Securities and Commodities Authority, the Financial Services Regulatory Authority or any other relevant licensing authority or governmental agency in the UAE. The content of this report has not been approved by or filed with the UAE Central Bank, the Dubai Financial Services Authority, the UAE Securities and Commodities Authority or the Financial Services Regulatory Authority.

Issued in the European Union by Muzinich & Co. (Ireland) Limited, which is authorized and regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. Registered in Ireland, Company Registration No. 307511. Registered address: 32 Molesworth Street, Dublin 2, D02 Y512, Ireland. Issued in Switzerland by Muzinich & Co. (Switzerland) AG. Registered in Switzerland No. CHE-389.422.108. Registered address: Tödistrasse 5, 8002 Zurich, Switzerland. Issued in Singapore and Hong Kong by Muzinich & Co. (Singapore) Pte. Limited, which is licensed and regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Registered in Singapore No. 201624477K. Registered address: 6 Battery Road, #26-05, Singapore, 049909. Issued in all other jurisdictions (excluding the U.S.) by Muzinich & Co. Limited. which is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales No. 3852444. Registered address: 8 Hanover Street, London W1S 1YQ, United Kingdom.